Photography, Art and Lifestyle. Aserica is Asia, America, and the Whole World in between

ONE SUMMER BY CARLA DELAPORTE

Freedom you feel on a random track, on a country road leading to the sea. The sound of the waves, the colour of the sky fading in the blue of the ocean. The Sun on your skin, burning. the carelessness, the smiles, bodies bonding together, we desire and love each other. Stones thrown in the sea, the sand covering everything. The poetry of sunsets, the smells of our childhood, the familiar landscapes. The scent of suntan oils, spices from the South of France. The stillness of night after a long summer day. Boats leaving and returning, wet clothes. Nature whispering “I am right here with you”. The lightness of being, the lightness of time.

The tale of a summer we would like to last forever.

In a world of high-res everything, and the notion that “best quality is always best,” Tablazon specifically shot his images using mobile phones. He started venturing into photography and video at the time high-quality imaging was not affordable and accessible in his country, and other than his fascination with low-resolution imaging technologies when it comes to translating memory and affect, Tablazon says his interest in these modes also stem from the fact that high-resolution photography and high-definition video may not be as default or matter-of-fact and ubiquitous in the Philippines and the rest of the so-called Global South as they might be in the more privileged parts of the world, and the mere choice of which camera to use already carries a lot of political and economic implications. His body of work has extensively involved analog video, mobile phones, consumer-quality cameras, degraded negatives, xerography, pirated film DVDs, and CCTV.

“Mostly shot using 2G and android phone cameras, Holotype is a series of diptychs that notate place and the human body in both the natural and fabled contexts of anthropology, natural history, geology, and architecture. These representations poised as tableau-vivant pairings aim at probing and reworking the codes and rhetoric of colonial naturalist and ethnographic discourse, offering indices to contact zones and encounters, and to the long and complex ‘romance’ between colonizer and indigene (and their often permeable borders) within contemporary and fictionalized images. The series seeks to explore the convolutions of representation in the name of empire and truth-making, in the blurred lines between art, science, and superstition, the relationship between epistemology and colonization, and the intimate link between fascination and violence.”

GREECE ON FIRE BY BENJAMIN GERULL

PIn Greece on Fire, German photographer Benjamin Gerull documents the haunting aftermath of wildfires in southern Greece, focusing on the Peloponnese region near Zacharo. The series captures scorched forests, smoke-filled horizons, and landscapes stripped of life, turning environmental catastrophe into stark visual testimony

The photographs were produced as part of Gerull’s diploma thesis in 2008, following one of the severe fire periods that regularly affect Greece during the summer months. Rather than focusing on flames or human drama, Gerull’s images emphasize silence, scale, and destruction, revealing how fire reshapes entire ecosystems. By treating the burned terrain as a landscape rather than a news event, Greece on Fire stands as both a documentary record and an artistic reflection on climate vulnerability, land use, and the recurring cycle of Mediterranean wildfires

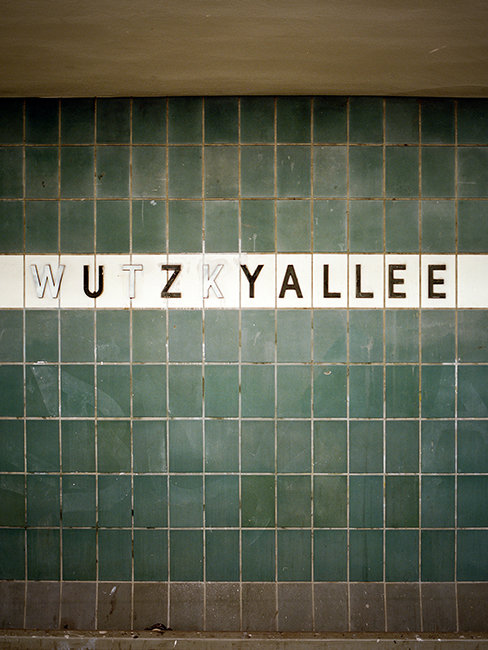

CHALLENGING PREJUDICES; GROPIUSSTADT BY LUKAS FISCHER

German photographer Lukas Fischer discusses his latest photo series focusing on Berlin’s Gropiusstadt with ASERICA.

The massive modernist housing project, named after Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius, covers 2.66 km2 and houses 36,000 people. While Gropius envisioned the semi-circular bulk as “orderly and calming through unity,” the area gained international notoriety as the home of Christiane F., Germany’s most famous drug addict. Fischer’s images explore the contrasts of this vast West Berlin neighborhood, documenting the life within its concrete framework.

1) Just looking at your work gives a real insight into Gropiusstadt, can you please tell us what drove you to shoot a story about it?

I grew up in a small village in the countryside, near a bigger town called Hanover. Every day on my way to school I passed the “Ihme-Zentrum”, one of those 70’s modernism residential and shopping projects, and I always asked myself how it would feel to live in there. For some reason, I never attempted to enter the towers, perhaps because the ground floor shopping area was frightening enough. Years later while studying in Berlin, I was working on a university project and had an appointment in the centre of the Gropiusstadt. At that point, I hadn’t heard about it but I was massively impressed by the place. All of my old questions about these types of residences popped up again, but now I was old enough to explore them and try to get inside.

2) After the release of the book ‘We Children of Bahnhof Zoo’, followed by the gory biopic Christiane F, do you think the modernist Gropiusstadt became symbolic of a glamorous underworld of drugs and prostitution in the 80s?

From an outsider’s perspective, I would say yes. The Gropiusstdt definitely became a symbol for the failure of these huge modernist style projects and the success of Christiane F.’s book made it known beyond Berlin’s borders. For a while, part of the Gropiusstadt was one of a few “no go areas” in Berlin. It still has a bad reputation, even though it’s getting better. When I started to photograph in 2011 a lot of people warned me not to go there, but in my experience, it is not dangerous at all. Of course, you meet a lot of youngsters – they are living there after all! On my visits, I met an old man, who worked as a bailiff in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s and often had to deal with Christiane F.’s parents. He told some interesting stories about the development of the whole area that offered a refreshing perspective. He and his wife were the first inhabitants of one of the first buildings and still live in the same flat today!

3) What kind of impact does Gropiusstdt represent for Berlin youth nowadays?

None. A few years ago, another huge 60’s development, the “Märkisches Viertel” became famous because some Berlin rappers grew up there. The attention moved over.

4) Is there a stigma attached to the residents of Gropiusstadt from other Berliners?

I think it depends on who is asked. For all the people who read Christiane F. in the 80’s, maybe yes. For all the younger generation of Berlin and those who have recently arrived at the city, I’m pretty sure it will mean nothing. They have probably never been there or even heard of it.

5) When I look at today’s suburban utopian architectural projects from the 60’s that were destined to low middle-class people with a mix of professional categories, however, they brought a comfort that most people never had before (hot water, separated rooms for children, elevators…) I realise that in some countries like France those projects quickly became ghettos, an outcast community with extreme poverty and violence, would you view Gropiusstadt in the same category? Are the crime and poverty rates higher in such neighbourhoods than others in Germany?

Yea and no. It’s not comparable to the things you see and hear about from some of the French “Banlieues” (I haven’t been there so far), but the fact that most of these areas are far from the city centres, bringing almost no infrastructure, besides the one big obligatory shopping mall, makes them unattractive for those who are looking for a hip and urban surrounding. The result is obvious – especially in poverty rates.

6) Your interior pics challenge the perception of what one might imagine a ‘ghetto neighbourhood’ looks like – it seems that people live there in cleanliness and order, even public spaces don’t look run down, apart from the odd bit of graffiti, it looks like a very liveable place. Was it your intention to show this side of the building and its inhabitants and challenge outsider perceptions? Or did you deliberately choose interiors that would antagonise the general perceptions people have of Gropiusstadt inhabitants?

My first intention was mainly to have an open view at the place, trying not to bring too many prejudices. What I found was an impressive variety of ideas and visions of the inhabitants for their life. When the Gropiusstadt was build, it was a dreamlike temple of modernism for all those who moved there. Coming from run down old housing structures, here they found automatic heating, their own toilets and bathrooms in the flats and elevators – and all this in a modern, futuristic setting. On my walks through the area, I met a lot of older people, most of them living there since the beginning in the mid 60’s. They still remember the heyday of the Gropiusstadt and try to keep the essence of it alive because they still enjoy living there. On the other hand you have a huge group of inhabitants with different heritage and backgrounds, following other visions and ideals that often clash with those of the elderly residents. In my work, I tried to find and show both sides.

7) Do you consider your work to have a social agenda? Or would you say you try to get beautiful images through places that are generally not considered attractive?

In all of my work I try to follow specific societies and often social agendas. Working on the Gropiusstadt was mainly a fight against my own prejudices and resulted in the idea of scrutinising prejudices in general. The contrast of what I’ve heard about it in the media and what I’ found myself was overwhelming. It is about showing my view as an alternative to the “No-Go-Area-Mainstream” belief.

8) Was it difficult gaining access to the people’s private spaces? Is it that you know someone living there already that you were able to get up close and photograph people?

When I started the project I entered the place as a foreigner. Fortunately I lived just 25 minutes away by underground so I went there almost every day over the course of a few months. Whenever I came across someone who seemed interesting I tried to get in contact and found most of the people were very open-minded and interested in my project. Also almost everyone I spoke to liked living in the Gropiusstadt and therefore had an interest in showing an alternative view of it. In most cases it took some time and several meetings to build up confidence, but in the end, it worked out well.

9) In your opinion did Walter Gropius utopia, succeed in making an area that was “orderly and calming through unity”, either in the past or now in the present day?

No. But I don’t think this is the fault of Gropius, who by the way was not included in the final planning. I don’t believe that planning and building megastructures for thousands can ever work out, all around the world you can see examples that prove this. I believe in the organic growth of structures with all their necessary coincidences.

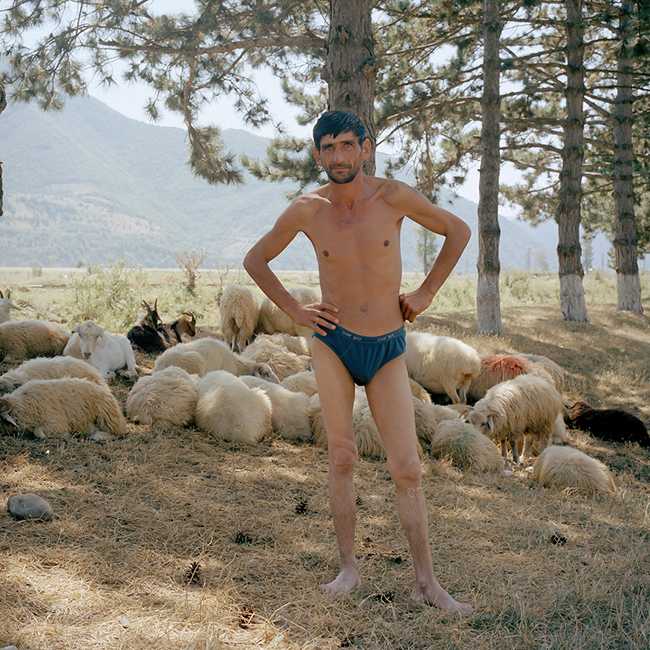

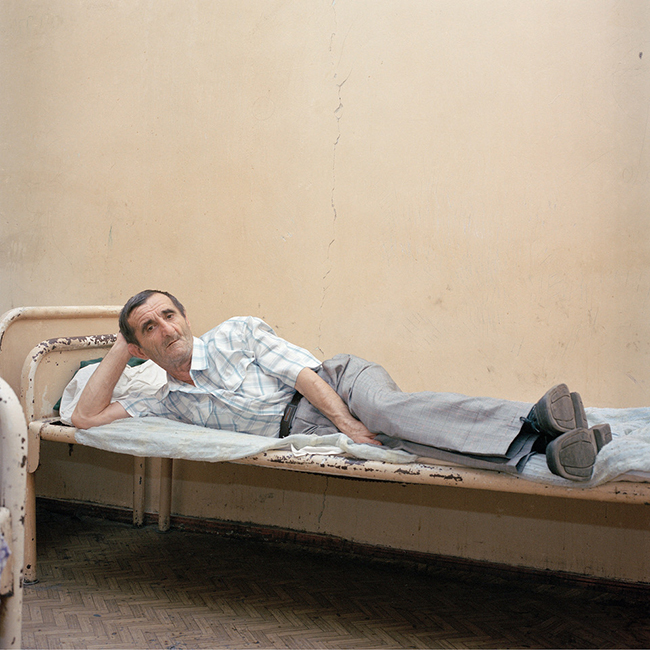

TBILISI BY CLAUDIO RASANO

Photography by Claudio Rasano, Interview by Matthieu Lunard.

ML: What attracted you to Georgia?

CR: I had the wonderful chance to get to know Georgia under the programme of a residency exchange programme of the Christoph Merian Foundation, Basel. I must admit that I applied for a residency in South Africa and was then selected for Georgia. The jury thought that my approach would be perfect for a stay there.

This was my first «prize»! So my journey took me to the city of Tbilisi. I was completely overwhelmed by the recognition – and then by the country and its people.

ML: Were you there with a special concept in your mind?

CR: I wanted to capture the ways in which people reflect their environments. For example inside a bath house, or the tropical institute.

ML: Nurses, bus drivers, firemen, butcher, workers, your subjects seem to be all all belonging to the people. Did you deliberately choose your subjects from this kind of background? Why?

CR: I don’t choose the people for my pictures, I meet them. And they catch my attention by little things like an expression on their faces, or a gesture, a word. It’s these little things that open up backgrounds and lead me to body of works about nurses, bus drivers, firemen, butcher, workers.

ML: How did you find them and convince them to pose for you?

CR: As I mentioned, I did not find them, they kind of found me. Most of the times, I don’t have to convince them, they genuinely want to pose for me. Before I take a photo, I build a relationship with the person by telling about my work and listening to their state of mind. I think, that approach comes through in my pictures.

ML: Can you please explain what kind place is the dormitory?, It seems to be a nursing home for poor old people, is that so? Are the nurses photographed working there?

CR: The place you are referring to is a shelter for men and women. I photographed the men within their rooms.

ML: You mix Portraits of people mostly alone with empty run down spaces. did you want to convey a feeling of loneliness?

CR: It is important to me to show the subject authentic and in its habitual environment. Only selectively, I extract the subject out of its environment, and I use no background in order to beware context or embellishment.

Besides the portraits, landscapes also form part of my series, as a reversed situation: the landscape emptied of the subject.

ML: What did you find there that was still visually present from the former USSR period and what would you say was the most Georgian thing you have shot? How would you describe their cultural identity? Are the people you met nostalgic of those times?

CR: This is a very difficult, also very politically loaded question, and I prefer not to answer it.

ML: Is there a caucasian identity that you wanted to express via your photos?

CR: Absolutely not, I don’t see people within the frame of a specific nationality. For me it is really more about exploring the relationship between spaces and humans. The Georgian series explores both the subject within the space and the space as a subject itself. Sometimes, I have conveyed the personality that these spaces hold and how they contrast with that of the actual person. Though the spaces may seem empty, they are truly full of personality and history. The interpretation is open to the beholder.

ML: Have you travelled to the other countries of the Caucasus? (Armenia & Azerbaijan) If so did you find a real Caucasian identity that link these countries together? How is it expressed?

CR: I prefer not to talk about cultural identities, I find to be the wrong person for that.

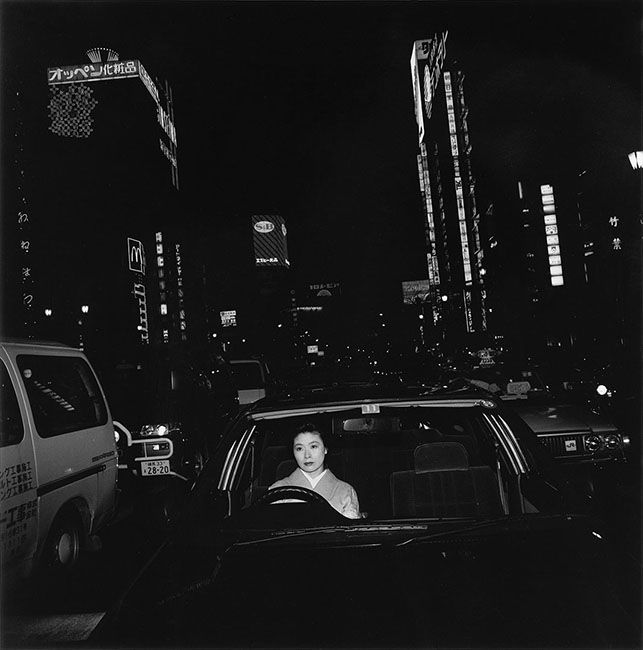

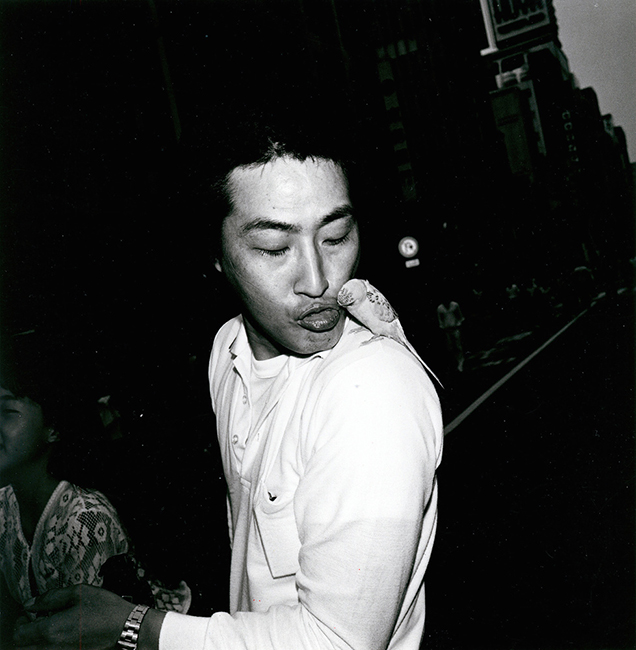

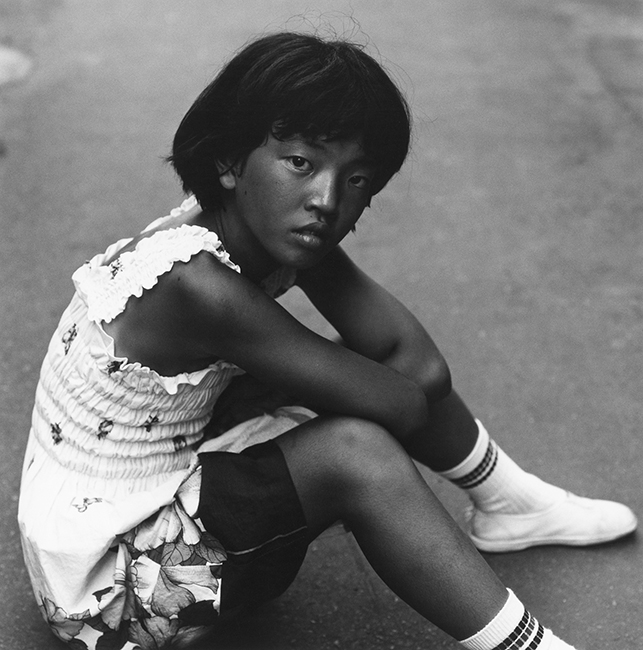

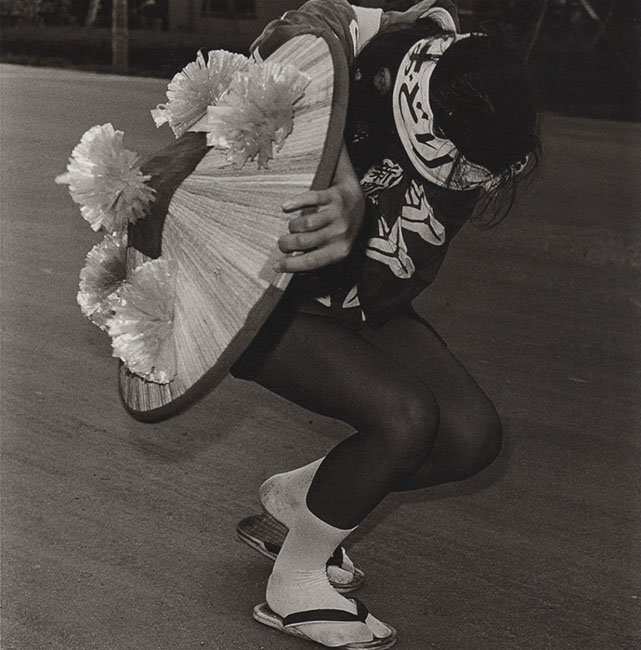

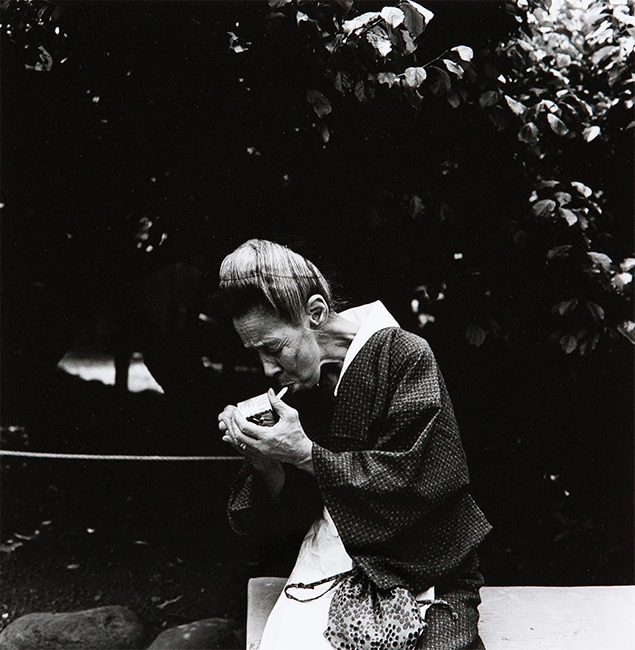

INTRODUCING ISSEI SUDA

Issei Suda was born in the spring of 1940 in Kanda, Tokyo. From an early age, he was drawn to the arts. He left Tokyo University to pursue his true passion, enrolling at the Tokyo College of Photography, where he graduated in 1962. During the 1960s, he worked as a cameraman for a theatre troupe, an experience that shaped his visual sensibility

In 1976, Suda published his first photobook, which earned him the Photographic Society of Japan’s Newcomer Award. Yet, unlike many of his contemporaries, his work received little attention from Western critics. His photography combined a sharp, investigative eye with a deep appreciation for Japanese traditions, while also documenting the transformations of a rapidly modernizing society. With a straightforward, unpretentious approach, he captured the world exactly as he perceived it.

Over the course of his career, Suda published numerous books and established himself as a significant figure in Japanese photography. Later, he shared his expertise as a professor in the arts department at Osaka University.

He passed away this year at the age of 78. At first glance, his work may appear deceptively simple—raw, direct, and fearless. But when we look closely at the breadth of his archives, it becomes clear: Issei Suda was a true master of his craft.

TARO KARIBE’S SAKHALIN ISLAND

Photography by Taro Karibe, Interview by Matthieu Lunard.

ML: Sakhalin Island in Russia is the country’s largest island. It is located just off the north of Japan .

At one point in time, Sakhalin Island had been claimed by both countries. Did you choose this island as your topic because of its close proximity to north Japan?

TK: Yes. Historically there had been quite active interchanges between Russia and Japan at the island, and I assumed the mixture of ethnicity and culture affected inhabitants. In spite of the fact that the island is one of the closest abroad of Japan, we don’t really know about how the life there and how inhabitants identify themselves, so I wanted to visit there and to confirm by my eyes.

ML: The island is a symbol of the Russo-Japanese rivalry, was there something of this topic that you were looking to capture there?

TK: Yes. I wanted to understand the importance of the island for both countries (Sakhalin island is not as much disputed as Kuril islands). Especially in terms of its natural resources.

ML: On Sakhalin remains a presence of indigenous people, named Ainu. Did you make the connection between the indigenous people that these countries share before you actually headed there?

TK: According to my research on Ainu people, it seems there is no community in the island any more. Although they existed there before, so I studied the history. There is a big community of the Indigenous people called Nivkh. I made contact with some of them before I visit Sakhalin, and captured their lives there.

ML: Places geographically located like Sakhalin often have a harsh climate which pairs with difficult living conditions. Did you feel that there?

TK: I visited there only in summer time, so I didn’t feel that actually.

ML: In your photos on the island we can see many scenes of everyday life. Often children playing or people walking down the streets.

Did you deliberately want to show a normal aspect of life? In particular, comparing normal life against clichés of living a more difficult life due to the location of the island.

TK: Yes, at first I wanted to show the real life there in documentary style. I ended up changing the direction to more arty street photography because I fell in love with the colors in Sakhalin. I wanted to show them as pure graphic with certain mood.

ML: We can guess from the light and the way people dress that you shot in summer. Did you specifically try to show a sunny side of the island? A search for a special light?

TK: Not really. Just because of the timing. This is an ongoing project, so I’m planning to go back there in wintertime to show the variety side of the island.

ML: What do you think you could have shown differently in winter? Would it have been a different social conception or vision conveyed by the different light and the coldness reflected in the images?

TK: I think I will express the ‘endurance’ and ‘melancholy’ by winter images. Since the island has been affected so much by history and politics. I want to show how people live in these kind of situations.

ML: Is your choice of framing body parts deliberate? What does it represent to you?

TK: The framing body parts is deliberate, and it represents my aesthetics.

ML: At Aserica we know you by your black and white, darker images from ‘Melancholia’ (2014), overexposed shots from ‘Cinders’ or LED lit street photos. In this series we see more natural light and sunshine. Was this a way to approach another style of photography?

TK: Yes, I always try to push myself challenging new approach. In this series I tried to concentrate on the sun light.

ML: Many of your works express something journalistic. From predictions for social or catastrophic issues like The Suicide Forest and After Shocks: Kumamoto Earth Quake (2016). Would you consider yourself more of a social reporter ?

TK: Not really. My main concern is to capture the human condition in psychological, philosophical and sociological perspective with personal perspective. My works looks very social, but actually it’s very personal. Actually, the way of approach is not really important for me. Sometimes journalistic, sometimes more artistic. I like to play with the selecting ‘style’. I always try to do new style and it helps me to enriches my perspective to the world.

ML: You said you loved Russia cause of it’s incredible contrasts and that it has lost its aim at creating an utopian society. This isn’t first time that you draw from this. In ‘ Melancholia ‘ you denounced the dystopian way of life and inhumanity of the city Tokyo. Has dystopia become a kind of obsession in your work?

TK: I think so. Exactly speaking, I’m obsessed by the feeling of alienation, isolation and emptiness. Since I was a child, I’ve only had a faint sense of being alive. There’s a huge gap between my consciousness and emotions. As long as I can remember I’ve felt like I were split in two, that I’m just a replaceable, empty existence.

ML: Did you loose faith in humanity creating an utopian society?

TK: I don’t know. Utopian society now we live is getting stuffy, although this may be because it’s transition period. I’d like to suspend my judgement.

ML: As seen through your lens, which dystopian society would you say you connect with most? Japanese or Russian?

TK: Apparently Japan, since it’s my homeland and everything of the country affected myself.

ML: You graduated with a bachelor of psychology, does it have an impact on how you perceive your images? How does psychology impact your images?

TK: Yes. I always try to make images that psychologically affect to viewer’s subconscious. I believe that the most strong point of photography is. It beyonds words and conscious. I want to push the power of photography.

ML: In many ways your concepts of image could be linked to the 19th century romantic movement characterized by its emphasis on emotion. Where art was an expression of the state of mind. Emotions like loneliness, depression sickness, sadness were the focal point of that era. Do you feel inspired by that movement?

TK: There are similarities between my way of work and the movement, but I don’t think I’m inspired by the movement. I was much inspired by existentialism, nihilism and surrealism.

ML: Would you say that your pictures are a metaphor of your own state of mind?

TK: Yes, and pictures are a medium that connects my conscious, subconscious and emotion.

ML: From your quote, “Through framing, I absorb the pain of the city and get to feel like I’m alive. Just like a wrist cut.” shall we assume that it hurts to photograph?

TK: Yes. It hurts mentally and physically. To photograph, I always have to be in the situation. I have to see, smell the reality and face to people. Sometimes I have to face the hard reality and have to get down to somewhere deep inside of me. It makes pain. Although thanks to the pain, I can feel that I’m alive.

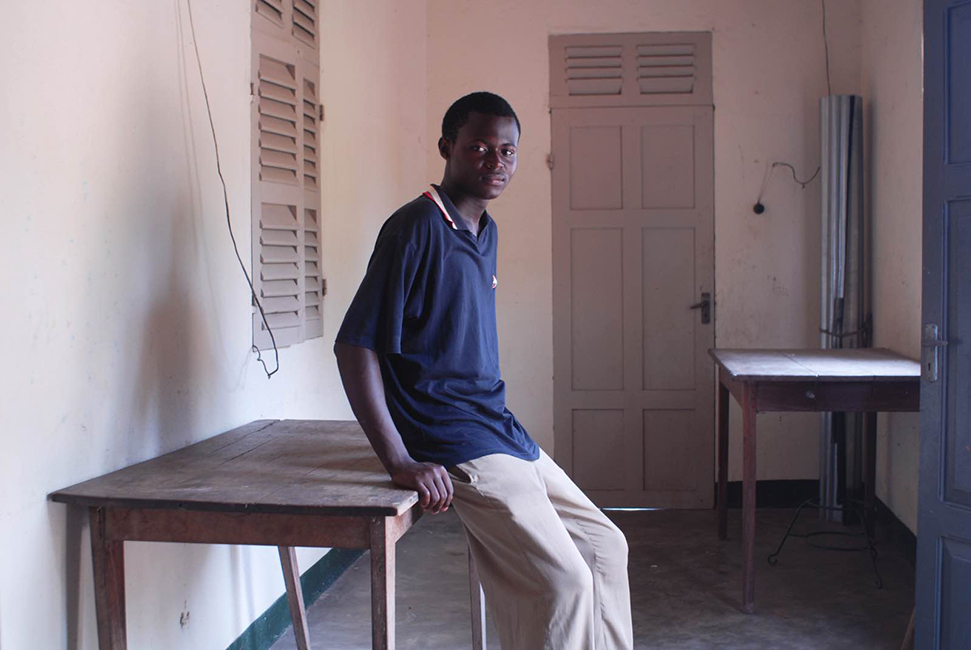

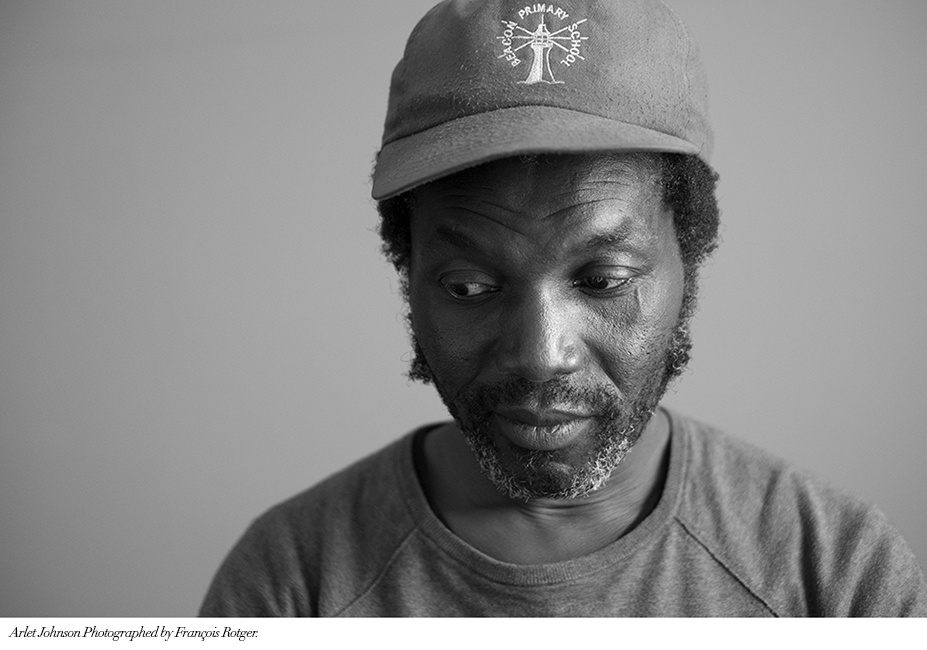

SOMETHING REAL BY ARLET JOHNSON

Not many people know Togo. It’s a small country on the west coast in Africa. That’s where I’m born. I moved with my family to Paris for my studies. After graduating in Law and Economics I went on a sabbatical year in South America – Brazil was one the countries I wanted to travel sinceI was able to read a world map.

From there I discovered my true passion for photography – back then I didn’t know much about the technical side of it, but the enthusiasm and inspiration were there. It came to be a great experience – I saw people and places differently under the prism of my Nikon FE2. I didn’t speak a world of Portuguese but with my camera I’d established a kind of conversation with people – for a trip that lasted almost a year. On my return to Paris I was invited to assist a friend in a studio, then I had to take my first steps as a photographer – mostly portraits – photography became my life.

I usually prefer to work with natural light or “available light” and focus more

on the subject. My main concern is to challenge myself to bring a sens of authencity and humanity to my models.

Today I’m working with digital – mostly colours picts – not so long ago I was shooting film – in black and white.

For theses past few years I’ve rediscovered my native country which I barely knew – it is now like a new land of experimentation.

It’s become vital for me to go back there as often as I can – somehow it has certainly impacted my work consciously or unconsciously.

My next trip to Togo will be to complete the work in progress, taking portraits of ordinary people, men at work, family and friends, simply showing the repetitive and often difficult daily lives.

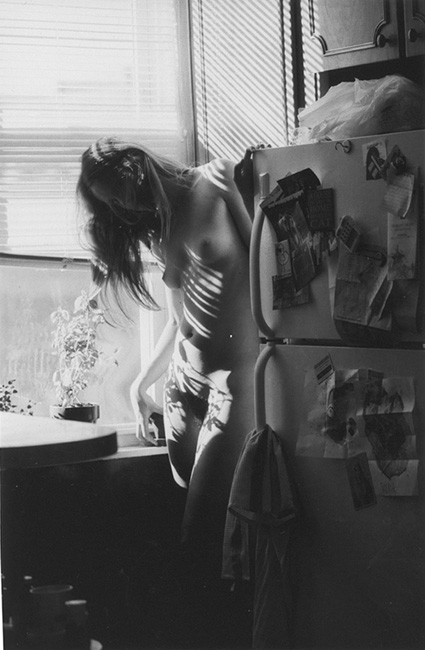

BEX DAY IS RAW AND CONTROVERSIAL

Aserica had the chance to interview the raw and controversial photographer; Bex Day. Bex’s work tackles issues of representation and marginalization, pushing back against normative constructions of beauty. Her work unapologetically and with utmost humanity promotes values of gender fluidity and diversity.

XP: Your work seems to be a fresh air in a photographic industry dominated by traditional andnormative representations of beauty. Representations of marginalized groups such as the disabled have historically been subject to a certain normative gaze where people from these social categories are turned into some type of spectacle. How do you go about photographing individuals from marginalized communities without it becoming some act of fetishization or act of ‘othering’?

BD: Thank you. This is always at the forefront of my mind whenever I engage in any type of documentary series focusing on marginalised communities. My whole ethos, which is central to my work, is about equality; treating everyone with respect, I truly believe we are all the same and my work is a way of taking this on and showing it to the world. (In this respect I am extremely interested in Buddhism and Zen teachings, which is how I expanded my knowledge on this topic).

It is of the utmost importance that everyone I photograph is happy with their image, besides that emotional connection is also vital and a collaborative effort – if the subject is not interested in the series or my work as a photographer then it will not work and it is better to not work together on this particular occasion.

XP: I have read in an article that you have a strict no-retouching policy. Could you elaborate on your decision to implement such a policy?

BD: In terms of strict it would only be in the case of my personal work, commercial work is always slightly different in this case which I can also understand as you are taking a step back from your “show” as you could call it, it’s a collaborative effort between you and a brand so it is also important to keep their needs in mind.

I used to work as the photo editor for PYLOT Magazine which laid the foundation for the decision to not retouch my personal work, as the publication’s ethos is all analogue photography with zero beauty retouching.

Challenging beauty ideals plays a huge role in my work. I seek to find something that someone may not consider beautiful in themselves and then spin it round and really change how they feel about it as it is often a negative feeling towards it because of what society imposes on us to make us decide what is supposedly beautiful.

It’s like that quote by the columnist Mary Schmich, which was later used in that Baz Luhrmann song, “Everybody’s Free to Wear Sunscreen”: “DO NOT READ BEAUTY MAGAZINES THEY WILL ONLY MAKE YOU FEEL UGLY.” It’s important to break rigid beauty ideals and challenge how people think.

There are constraints due to the fashion industry but I think it is becoming more and more open to change which is great to see. I am happy that more and more photographers are using street cast models, and ‘normal’ sized people; the more unusual is becoming more attractive, non-perfectionist ideals like blemished skin and quirky characteristics like bigger noses.

XP: How much of your work is informed by academic discourses within fields like for example gender studies or sociology? How do you go about researching your subjects before the actual photographing process? Is this something you do?

BD: A large amount, anthropology and sociology are important to me, my aunt often inspires me as she is a professor of anthropology and has helped me with various concepts.

I read a number of gender related books (both fiction and non-fiction) before embarking on Hen (which is being exhibited on March 31st in London to coincide with Trans Day of Visibility and will be showing for 2 weeks), the most poignant being Gender Trouble by Judith Butler, Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides as well as Trans: A Memoir by Juliet Jacques. Besides book research I’m very much into people and hearing their thoughts and opinions, particularly those I’ve photographed for Hen; it’s the experiences with them in their daily lives and the things they have told me about their experiences that has really enhanced my understanding of what it truly means to be transgender.

I come from a journalism background so research and narrative are also predominant within my work. I am also extremely interested in psychology which plays a large part in my role as a photographer.

In terms of specific subjects, we will meet before the shoot predominantly to see if the connection is there and it works (it usually always is because both parties are interested).

XP: What is process like casting the models for your photography? What do you base your decisions on?

BD: As I mentioned previously, emotional connection is important within my work.

I like to shoot individuals that have not been shot before because they ascertain this almost virgin-like quality that I find difficult to evoke when working with signed models. Their sense of awkwardness is so beautiful to me and usually they have no idea just how beautiful they really are. I like that kind of unearthed, undiscovered beauty. I was always taught to be modest growing up and I strive to find that in people I photograph now.

XP: What role do you think photography has in influencing wider social discourses on gender and issues like transgender acceptance?

BD: It is hugely important, I feel like text cannot emphasise the hugely in that sentence enough. It’s a duty to photographers to do something positive for the community.

Hen for instance came about due to the lack of ageing trans people shown in the mass media. It annoyed me and shocked me because their stories are really vital in educating and expanding our knowledge on the topic. Ignorance usually arises from lack of information.

I recently photographed my good friend Alex who is transgender which will be showing on Vogue Italia in November. The whole point of the shoot was integration; essentially looking past the fact that she is trans and focusing on her as a person, showing aspects of her personality. She said the shoot made her feel beautiful, accepted, classy and confident.

XP: In your biography it is mentioned that you are a self-taught photographer. What exactly does this mean? How did you go about teaching yourself photography? And what advice would you give to aspiring photographers looking to follow a similar route?

BD: I got very very bored during my journalism degree. My father was a journalist and I thought that was my path too. After various internships at huge publications I decided working in an office was not for me.

By my third year I decided to teach myself photography. I used the studios and dark rooms at university and spoke to the tech guys whenever I could. I snuck into some photography lectures too. I read every book I could about the subject. Then I started shooting age 21. I assisted Ryan McGinley in NYC amongst others in London, and dated a few photographers who taught me a lot too.

I would say use everything you have that could enable your career and don’t compare yourself to others too much. Focus on what makes you, you. Originality is key to success.

XP: And lastly, where do you see yourself progressing artistically? Which issues of marginalization will you tackle next?

BD: Progression wise I would like to continue to balance my fashion and documentary work side by side. I am about to move into my studio in London.

I am focusing on Hen completely at the moment as a lot needs to be done before the exhibition. I am sure it will also become a book at some stage.

I am also currently working on a zine of imagery titled Pattipola (in collaboration with Bruce Usher, creative director) I shot when I lived in Sri Lanka for a while. The zine is a reaction to my friend being sexually assaulted on the train there – there is a big issue with sexual assault in Sri Lanka so it is a homage to that. I was volunteering in psychiatric wards and took time away to compartmentalise and shoot this project afterwards.

TANYA!

Tanya Korotkova photographed and interviewed by Matthieu Lunard.

Tanya Korotkova is Russian model with a love for literature and self-discovery, Aserica recently sat down with her to talk about her childhood, inspirations and future.

AM: What is your name?

TK: Hi! My full name is Tatiana. But people call me Tanya, which is typical for Russian culture to shorten the name in this way.

AM: Where are you from?

TK: I’m from Moscow, Russia. I was born in a city just next to Moscow and with time moved to the capital.

AM: What is a childhood memory you think of fondly?

TK: Every summer holidays away from school, I was spending time in the countryside with my grandparents, which was a great relief. A change from city life. I loved the time my grandpa helped me create objects from the wooden boards, joined with some nails, turned into wooden look alike car objects and as well wooden polished seats for swings. Now that I’m 25 years old, I once again discovered the usefulness of giving a kid means and freedom to bring your ideas into something physically existing.

AM: How did you get into modelling?

TK: I was in Bangkok for almost a year when I lost the jewellery trade manager position at the company I work at that time. And losing it I faced the problem of getting a new source of earning and as I was not ready for the possibility of the company not extending my contract, I had no choice but to make things work quick. I tried teaching at Thai schools, been working as SMM in a company similar to the European «Wellness» but this made me feel like I’m doing an emotional and lifetime sacrifice every day when I stepped into the office. So that is when the casting and all this media commercial part came into my life.

First, I was super shy, I still am. I remember, my first casting for S7 Airlines my lips were shivering and I was not able to smile properly. So I didn’t take it. Then was just keeping giving my beliefs a chance of getting a lucky ticket. And acting approvals for many TVC just started to happen fast and multiply. If there’s a season, let’s say in Thailand it’s from late October up to May, skipping the rain 4 months of no jobs. If you are confident in acting (and 99% of a time the script does not even exist for the role and in case you get a role for 40K baht = 1.200 euros per day you will probably just have to smile and do some body movements, 1% still exist but its super rare that your role will be complicated) and a freelancer (cause «proper» agencies here still have more offers than freelance agents) you can still earn enough to live on this income. For the majority of European productions, it’s way more profitable to shoot in S-E Asia, cause it’s: a) cheaper (the budget for a tvc actor in western Europe about 3-4K up per day – in here 500-1500 euro per day), b) the country has many landscape options to offer etc.

AM: Who are the people that inspire you? and why?

TK: Some of them I never had a chance to meet, but I’m happy to be able to read their thoughts. My beloved one is Kafka «the castle» which with every new perusal gives me new ideas. I love to listen to interviews of the filmmakers (like Wim Wenders – his I listen to a looooot) to understand how they create and what makes them just simply do it. Recently I read the story of habits and hards work in the creative field of an American dancer, choreographer, and author Twyla Tharp. Then I did some research of her choreography on stage and was amazed by how people, especially in such industries, keep on following the path they ones picked up, to the very late years of their life. She’s 77 years old by the way and still in business.

AM: Where do you see yourself in the future?

TK: I’d love to write either fantasy novels or conduct research on society «social diseases» like apparel consumerism, over-consumption which leads to obesity and opens new markets of plastic surgeries and making people follow two path; the one of «i don’t care» and the one of «hooked on look». Or not making a choice in between those two, just doing both. Plus I would like to study the aspiration of the people that are into contemporary dance and learn where they get their inspiration from.

Project team:

Photography and post: Ira Condrea

Stylist and video production: Alexander Antoniu

THE SEASON: BRIANNA BEASLEY BY LAUREN WITHROW

Photography & poetry by Lauren Withrow.

Your heart beats from your chest, syncing with the mother birds that chirp from their nests, seeking their companions. A crisp fall breeze slips the through invisible holes in the window sill and the light filters through, illuminating your face as we wander the rooms of my grandfather’s home.

Two years have gone by.The Texas air is clean. It is what our lungs feel most comfortable with. Our movements mimic each other and our exchanges remind me of ones that only occur between decades of friendship. My mind slips, imagining thirty years from now, wrinkles filling our faces, bones starting to ache. Together we will always remember these days spent during our youth, free of the responsibilities of adulthood, enjoying the minutes as they pass us by.

Each leaf falls slowly as the seasons changes. Pecans cover the earth, we gather them, and together we sit, cracking one shell at a time, enjoying the words shared in between indulging in the fruits of my grandfather’s tree. Another year will pass, and again we will sit here, enjoying the memories only you and I will share. “

CONCEPTUAL LO-FI FASHION

Тинереце mixes Soviet aesthetics with contemporary fashion

Тинереце.raw is a conceptual lo-fi photo project which aims to embody the spirit of contemporary youth culture. It is produced in Chisinau, Moldova. The name is derived from the Romanian word “tinerete”, meaning youthfulness. «тинереце» is the Moldavian adaptation of the word – springing out of the Cyrillic alphabet and used before 1991 specifically for Romanian words

The conceptual driving force behind the project is the ambition to show new aesthetic senses and ideals. The project establishes connections between Soviet Architecture, vintage and contemporary sportswear and the habits of the new generation, who shape their own identity by appropriating world fashion trends while mixing them with territorial features unique to their region.

Тинереце.raw is the first project in the brand family Тинереце. All photos are staged in Chisinau, Moldova and taken between April and June 2018.

Project team:

Photography and post: Ira Condrea

Stylist and video production: Alexander Antoniu

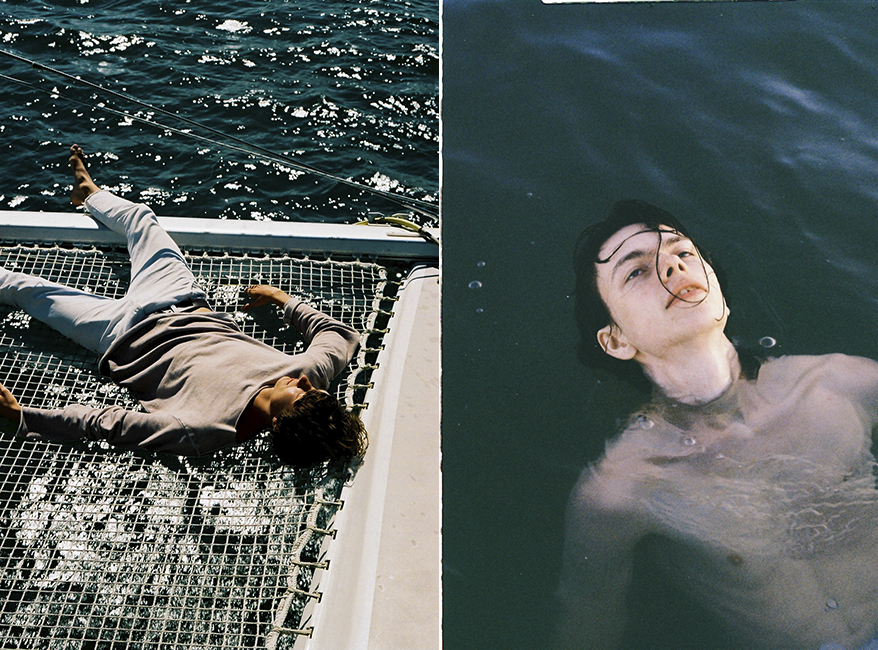

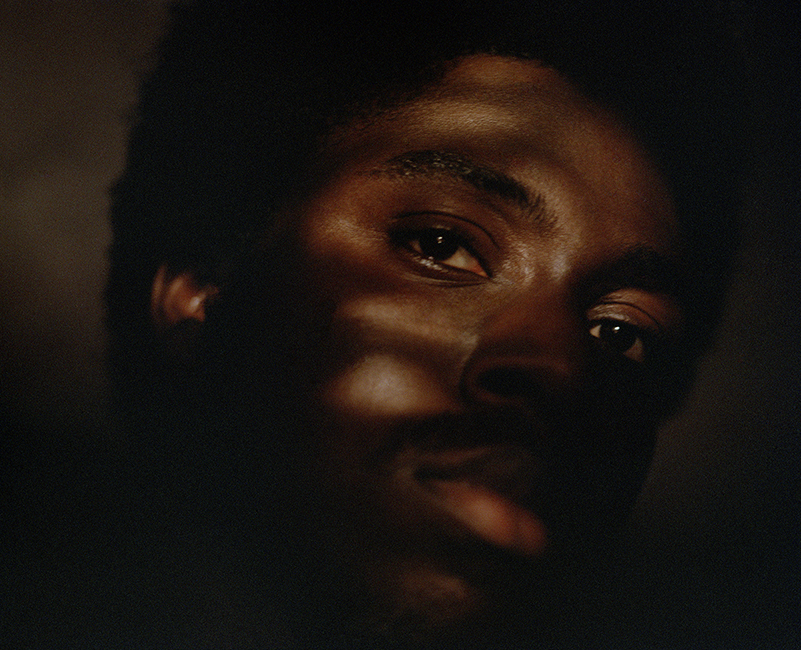

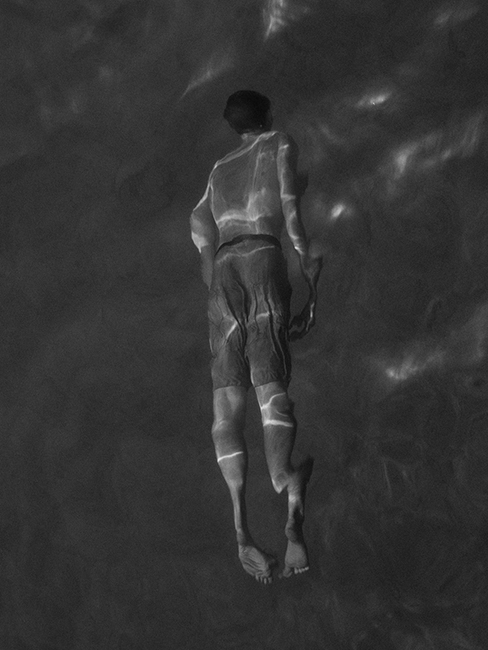

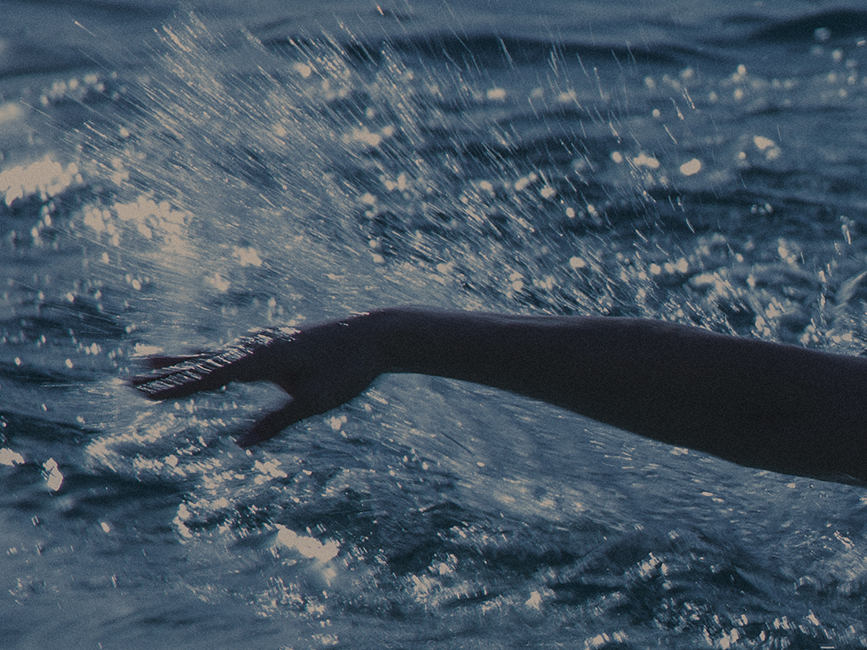

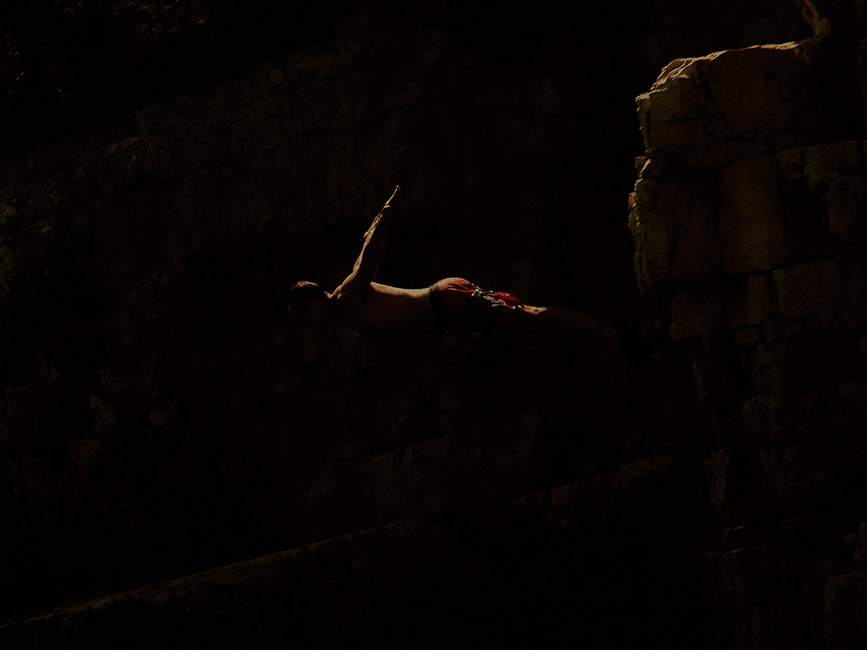

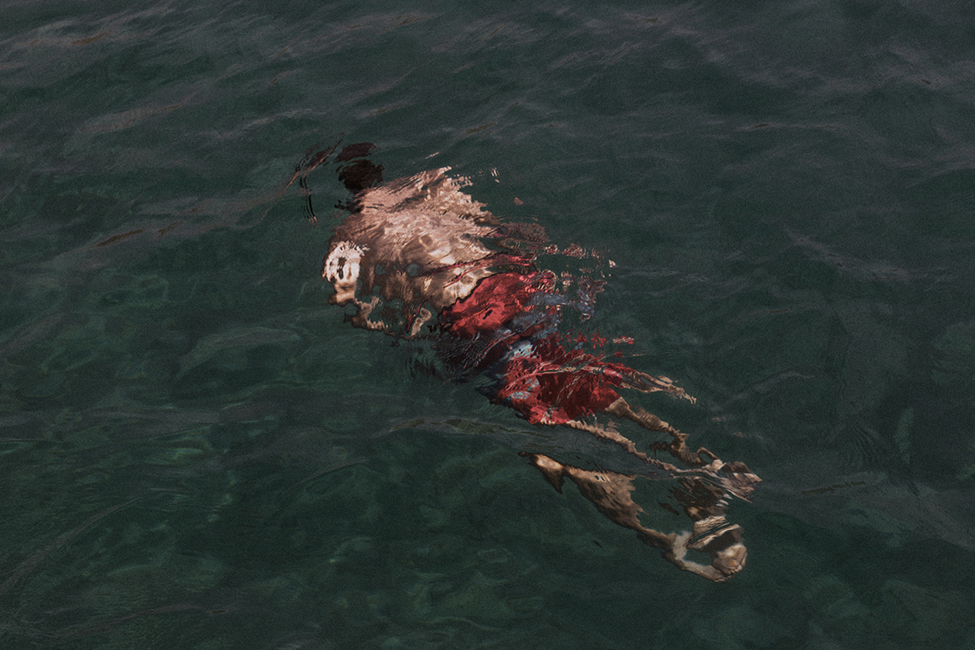

A MIDSUMMER’S DREAM

The colors, vibrations, and shades of the sea. The swimmer, drifting in and out of water, endlessly drawn towards this magical, mysterious, and infinite element.

In this story, I explore the visual interactions between water and the human body: the sensuality of wet skin, the abstraction of the body underwater creating new landscapes… this ballet between the swimmer and the sea, ever so mysterious… and the possible, reversible change in consciousness when one dives too deep,

sharpening the senses and causing visions, hallucinations.This project grew out of a long process of revisiting photographs I took one summer when the idea for this story emerged. I first created Songe, then Shades of blue before it dawned on me to blend both series so as to design a fuller narrative. Part of my creative process was to become that swimmer, plunging back into my own sea of images, looking and going deeper, searching for new visions.

Anne-Sophie Soudoplatoff is a French photographer based in Paris, working on different photo projects as a freelance artist, while directing photography workshops. She graduated from Gobelins, school of images, in 2015 after obtaining a Master’s degree in cinema.

Her work was shown in various galleries in Paris (Galerie Madé, Galerie Claude Samuel) as well as abroad. It was recently awarded the Prix jeunes talents des agents associés, selected to be part of the 30 under 30 women photographers 2019 edition curated by artpil and featured in the Incadaqués International photography festival Open call 2019.

In her photographic work, Anne-Sophie explores a world between reality and fiction, working mostly on short stories and visual poems.

Inspired by cinema, as well as some of the pioneers of color photography, she places a particular focus on atmospheric scenes, light, colors, textures, and framing. Ephemeral lights appear to her as timeless spaces, unveiling the innermost, mysterious facets of beings, shrouding them in dreams.

By juxtaposing her images, she lets latent echoes emerge between them, in order to create new spaces and devise her own stories.

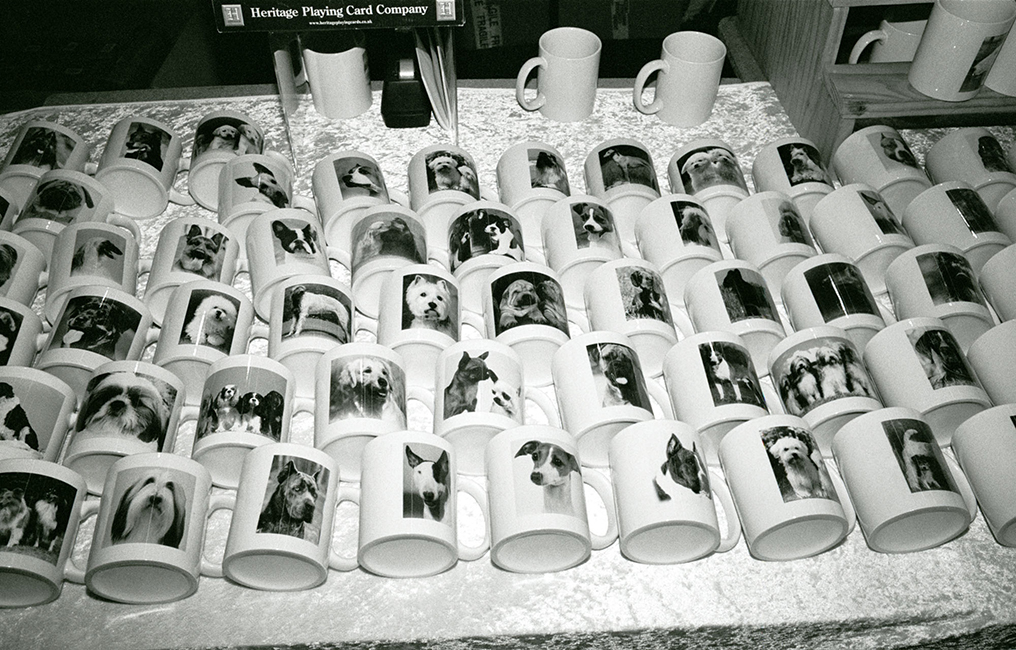

DOGGIE STYLE BY FABIEN BARBAZAN

Fabien Barbazan first found his photography passion while working with famous French rock photographer, Claude Gassian. From there he entered the fashion world with a stint as a photo assistant before finding his feet as a fully fledged fashion photographer with various magazines. Fabien discovered the works of fellow photographers such as Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and

William Eggleston, which sparked a renewed sense of inspiration in him to refocus his work around a photography style that is more intuitive, spontaneous, capturing real moments in the world around him and less of the curated scenes that often grace the pages of fashion magazines.

Taking a stroll through a park in Estoril, Portugal one day, Fabien spotted a dog show and was struck by the fabulous owners and preened pooches! The photo series Doggie Style captures the preparatives happening behind the scenes, drawing parallels to the effervescence before a fashion show. Photographed in a non-intrusive manner, the images show the proud owners’ dedication and passion for their pets, sometimes with a dash of humour! Fabien told Aserica, “It is interestingto see that a true symbiosis exists between people and their dogs. I wanted to explore the notion that animals are not superior to humans in these photographs”.

Doggie Style shows photographs from the Portuguese dog show and a few more, mostly around Paris, France.